Today the FDA announced it’s banning food dyes in Skittles, Cheetos and other packaged products, and MAHA is ecstatic. The leader of this effort, Calley Means, calls the forces he’s facing ‘demonic’ and the FDA’s actions ‘historic.’ At the same time, Calley is strangely quiet on the fact that in the past ten months, over nine million children have been injected with the latest version of an experimental gene product with no long term safety data, and the government not only supports this but expects this. According to CDC guidelines, all babies are expected to get three Pfizer mRNA shots by the age of nine months.

When I spoke with Calley during the Danny Jones podcast, he assured me he had no interest in securing a position with President Trump. Apparently, he was not sincere, as he is now an official special government employee, charged with assisting HHS director Robert F. Kennedy to embolden the MAHA movement. Calley, who convinced Robert F. Kennedy to drop out of the presidential race and endorse Trump, has much to gain from his high power political position.

Calley Means’ company TrueMed stretches the applicability of Health Savings Accounts (HSA) and Flexible Savings Accounts (FSA) to include a wide array of wellness products traditionally not eligible for purchase using HSA/FSA funds. Means has been pushing for policy changes to support the broader use of HSA/FSA funds for products such as cold plunge systems, vitamins, and health tech gadgets.

HSA/FSA accounts offer the advantage of reducing taxable income, allowing one to pay for qualified medical expenses with pre-tax dollars. Though only 10% of the U.S. population had an HSA in 2022, the market has huge potential for growth. Total HSA assets reached a record high of $123.3 billion in 2023, marking an increase of nearly 19% from $104 billion in 2022. For 2025, HSA limits are $4,300 (individual) and $8,550 (family), and FSA limits are $3,300.

Though growing, these tax savings plans have not been widely adopted by the American public as only people with high-deductible insurance plans are eligible. In general, HSA/FSA holders tend to have higher incomes, better education, and more stable employment in industries where high deductible health plans are common.

Qualified medical expenses for HSA/FSAs as defined by the IRS include medical care, doctor visits, hospital services, surgery, lab fees, imaging studies, prescription medications, dental and vision care, medical equipment and supplies, preventive care (vaccinations and preventive screenings and check-ups), mental health, ambulance services, travel expenses primarily for and essential to medical care, over-the-counter drugs, acupuncture, chiropractic care, physical therapy, breast pumps and supplies related to breastfeeding. Less common but eligible covered services include service animals, special education, genetic testing and home modifications (e.g., ramps for wheelchair access).

“Wellness” products, like fitness equipment, supplements, and health tech, do not automatically fall into the category of qualified medical expenses. TrueMed has figured out how to overcome this obstacle, pushing through approval of coverage for unconventional health expenses by writing letters of medical necessity (LMN).

TrueMed customers interested in purchasing a product off their website not typically covered by HSAs complete their online health survey; a licensed provider from their network reviews the data and issues an LMN.

The LMN is submitted to a HSA administrator for approval. (HSA administrators include banks, credit unions, insurance companies, investment firms, and specialized HSA management companies.) While the IRS doesn't directly approve individual HSA benefits, they set the guidelines for what constitutes a qualified medical expense. The HSA administrator is the gatekeeper and interprets these rules, and only in the case of an audit would the IRS check if the expenses were indeed qualified.

TrueMed generates revenue through transaction fees, service fees for LMNs ($30 per letter), partnership fees, data collection and sharing, and subscriptions. Similar to how other payment processors like PayPal might operate, where they take a percentage or fixed fee for each transaction processed, TrueMed charges a fee for each item purchased through their website using HSA/FSA funds.

By facilitating and processing a large number of transactions and health consultations, TrueMed could potentially leverage anonymized, aggregated data to sell to third parties.

With an increasing array of products eligible for purchase using HSA/FSA funds, merchants are looking at billions of dollars in potential revenue. Merchants report that by allowing HSA/FSA payments through TrueMed, they see an increase in AOV. Average Order Value (AOV) is a key performance indicator (KPI) used in e-commerce and retail to measure the average amount spent each time a customer places an order. With a higher AOV, each transaction brings in more revenue, which can lead to higher overall sales without necessarily increasing the number of customers or transactions.

TrueMed has partnered with at least twenty-three health-focused companies. Using the allure of tax savings, customers are encouraged to spend more on an array products and services promising better health. Though most are could be considered potentially beneficial, very few products and services offered through TrueMed are scientifically proven to improve health.

Eight Sleep

One glaring example is TrueMed’s partnership with Eight Sleep. Announced in June 2024, TrueMed claims customers can save up to 40% on these products by using pre-tax dollars for “sleep wellness.” Eight Sleep uses AI to monitor “bio-signals” during sleep, claiming to enhance recovery and rest.

Eight Sleep tracks sleep stages, sleep efficiency, sleep duration, sleep latency, and "toss and turn” (movements during sleep) and monitors heart rate, heart rate variability (the variation in time between each heartbeat), and respiratory rate.

Apart from gathering data, one of its beds automatically elevates the bed's position if it detects snoring, and it monitors room conditions like temperature and humidity to adjust the bed's settings for “better sleep.”

Eight Sleep generates a daily sleep fitness score, providing users with an overview of their sleep quality and suggestions for improvement. The system's app then uses this data to offer sleep coaching and insights.

David He, Vice President of their research and development, stated the company recently ran a study over the course of a month with 10,000 of its members, claiming it was already the largest sleep study in history. David remarked, “We can figure out what happens in real-time, with real world evidence, then package what we learn into the model, ship it, and see what improves the next night when people sleep.” The data collection sounds amazing, but the company has not shared the results of this large study to the public. Prior to Eight Sleep, David worked for Alphabet’s life sciences company, Verily as head of Health Monitoring Devices.

Despite access to an enormous amount of data, the company has published only one study, "Sleeping for One Week on a Temperature-Controlled Mattress Cover Improves Sleep and Cardiovascular Recovery” (Moyen, N.E. et al. Bioengineering 2024,11, 352.) This small study of 56 subjects showed a significant reduction in heart rate by approximately 2% and an increase in heart rate variability by 7% when sleeping on the Pod compared to without it, as well as a significant decrease in perceived sleep onset latency (not actual sleep onset latency) and an increase in thermal comfort. This is the extent of the data. I’m not aware of any studies showing that a reduction in heart rate by 2% during sleep has any impact on overall health.

The two most common sleep disorders are chronic insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea, impacting approximately 10 - 20% of adults. Presumably a company claiming to improve sleep health with access to an enormous amount of data would demonstrate efficacy in mitigating these two sleep disturbances. In Eight Sleep’s single published study, key measures of insomnia - total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and latency to sleep onset - did not significantly change with their system. And despite their subjects using home sleep tests multiple nights, the company did not publish its data on snoring, oxygen level, and abnormal respiratory events.

David He and Eight Sleep’s co-founder, Matteo Franceschetti, have indicated plans to test sleep aid supplements across its customers, with the ultimate goal of working with the FDA to test the effect of pharmaceutical products on sleep. Matteo said he aspires to develop the “Ozempic for Sleep.”

The marketing hype surrounding their product leads one to believe the high-tech Eight Sleep mattress is the ultimate answer to a good night’s sleep. The claims, fluffy as they are, are carefully crafted to avoid legal troubles - the only concrete promise the company makes is that its mattress will give you up to one more hour of sleep every night. This equates to (up to) fifteen days of extra sleep per year. To add a veneer of credibility, Eight Sleep has leveraged influencer endorsements, particularly from high-profile athletes, tech enthusiasts, and health advocates.

People’s desire to get a good night’s sleep presents an irresistible profit opportunity for companies in the sleep sector. Eight Sleep has garnered significant financial backing, raising $86 million in a Series C funding round in 2021. Rumors swirl that Eight Sleep's valuation is now over $1 billion, making it a "unicorn" (a startup valued at over $1 billion). Eight Sleep was named in Fast Company’s “Most Innovative Companies of 2018” and was recognized twice in TIME’s Best Inventions of the Year. Its co-founder Matteo believes his company “owns sleep” and will hit a trillion dollar valuation.

The cost of an Eight Sleep mattress ranges from $2,495 - $3,495, depending on the model, size, and current promotions. To guarantee ongoing revenue from its customers, Eight Sleep requires a paid subscription (ranging from $15 to $24/month) to access most of the Pod's functionality, including sleep tracking and variable temperature control.

Is it possible to buy a good night’s sleep? Better sleep is a worthy health goal, and one that many are willing to pay top dollar for, assuming the pitched product actually works and has data to back up that claim. Eight Sleep brags about having plenty of data - but oddly, the company has been shy about sharing that data. They’ve only publicized one limited and self-funded study that does not translate into better sleep or daytime health. The study did not show the beds lengthen sleep time, decrease time to fall asleep, or improve nighttime oxygen levels. Poor sleep, from insomnia or sleep apnea, is strongly associated with impaired daytime performance and increased risk of heart disease - the company has not presented data showing its product improves these measures.

Apart from not showing any real benefits, the company fails to disclose two potential harms their product could cause - mold and EMF exposure.

Eight Sleep uses water to achieve cool temperatures. Users of Eight Sleep have reported leaks; if leaks go unnoticed, moisture could accumulate, which is ideal for mold growth. Even without leaks, water inside the mattress that isn't regularly treated or changed can become a breeding ground for both bacteria and mold, and if the mattress is stored in a damp or humid place, mold could grow both inside and outside the mattress.

Mold exposure can lead to various health issues, including allergic reactions, respiratory problems, skin irritations, and in some cases, more severe health conditions if it's a particularly toxic mold type.

A customer on Reddit recently posted, “Hi everyone, I just wanted to let you know that you should be really careful about mold. Our mattress cover leaked, it must have been a very small leak, and destroyed our bed. We spent over $5K with eightsleep at the end of 2021 and it hasn’t even been 3 years. We got the full set up- mattress, frame, pillows, sheets, etc. The mold ruined our mattress topper (not bought at sleep 8), our mattress and obv mattress cover is broken, and fitted sheet is gross too, we left on vacation for two weeks and came back to the bed stinking.”

Another concern is the potential harm of sleeping in a bed of EMF. Non-native electromagnetic fields (EMF), also referred to as artificial or man-made EMFs, are fields generated by wireless devices. Concerns about their potential dangers arise due to their artificial nature and the ways they differ from natural EMFs (e.g., those from the Earth's magnetic field). Non-native EMFs may cause oxidative stress by increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells, potentially leading to cellular damage. Studies suggest prolonged exposure could lead to DNA strand breaks or other genetic alterations. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified non-native EMFs as "possibly carcinogenic to humans" (Group 2B) due to potential links to gliomas (a type of brain tumor) and acoustic neuromas. Young individuals may be more vulnerable to EMFs due to their thinner skulls and rapidly developing tissues.

EMF exposure has also been linked to altered melatonin production and changes in brainwave patterns, leading to insomnia or irregular sleep patterns. There are concerns that excessive EMF exposure could contribute to issues like memory loss, reduced concentration, and other cognitive challenges.

Eight Sleep’s Scientific Advisory Board includes three scientists who have remained silent on these risks - Andrew Huberman, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and professor at Stanford School of Medicine, known for his work in brain development, brain function, and neural plasticity; Matthew Walker, Ph.D., a leading sleep scientist, author of "Why We Sleep," and professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley; and Peter Attia, M.D., a physician who like Calley’s sister, Casey Means, did not complete his residency, but has used his medical degree to become a very successful health influencer.

Casey Means and Levels

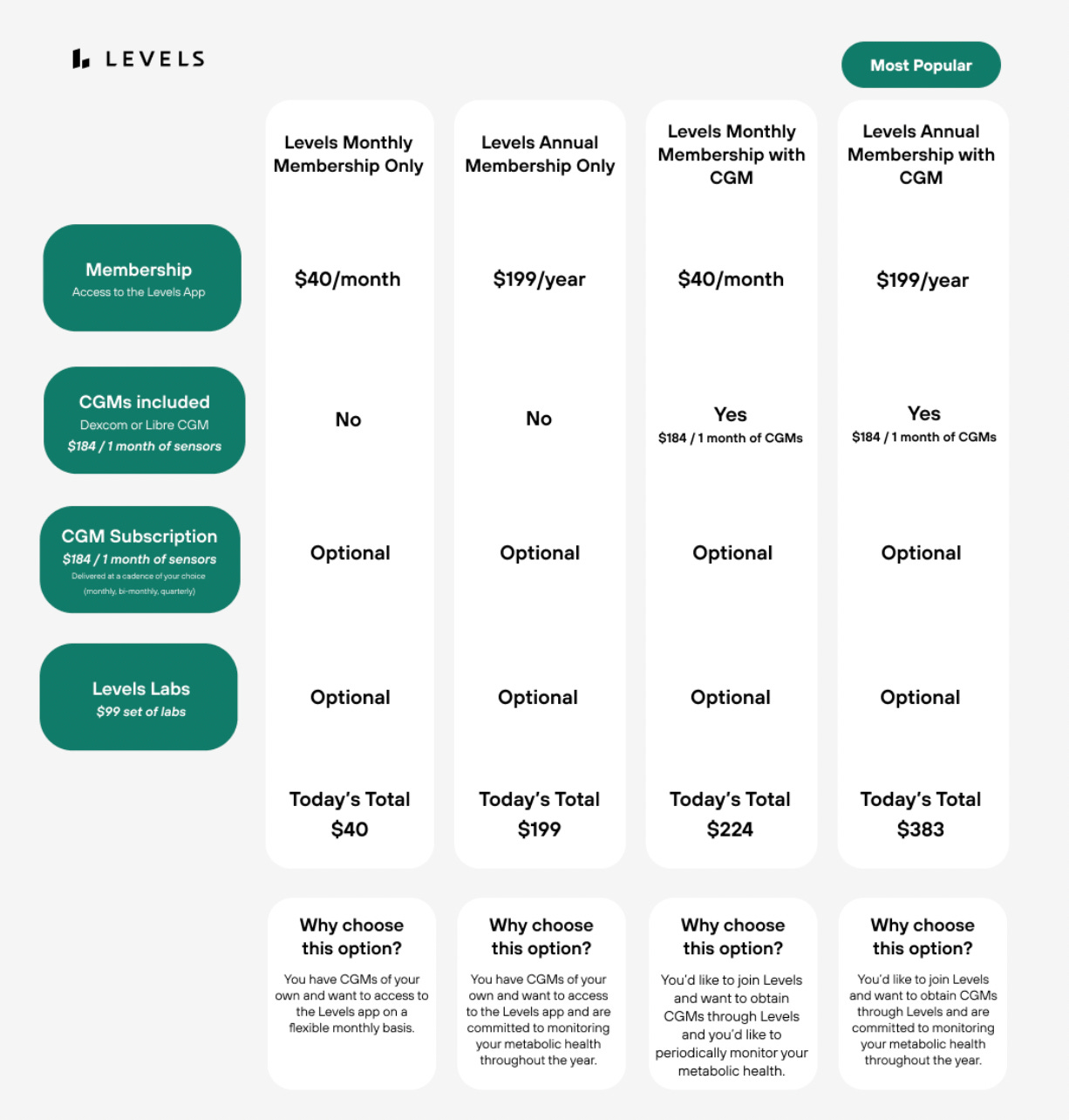

Dr. Casey Means dropped out of her Stanford otolaryngology residency and in 2019 created a company called Levels. Levels sells health-focused online memberships that include CGMs (continuous glucose monitors), and nutrition advice. Subscribers can pay up to $383 for an annual membership that includes two CGMs (cash price is estimated to cost approximately $75 each.)

Patients with diabetes use CGMs to monitor their blood glucose levels, and CGMs must be prescribed by a doctor. Levels uses doctors to prescribe CGMs, but the customers don’t meaningfully interact with these doctors. Careful to protect itself legally, Levels explicitly says it is not a healthcare provider, stating in its terms of service, “None of the services Levels offers are intended to be used to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease or medical condition. By using the Sites and Services, you agree that you will not attempt to use or rely for any medical purpose whatsoever.”

None-the-less, the company contracts with physicians willing to prescribe these devices without actually seeing or interacting with the members. After members complete an online medical consultation form, nameless doctors review the information and prescribe the devices. Given the purpose of CGMs, many of these members are presumably diabetic or at risk for diabetes yet have no direct interaction with the Levels doctor prescribing the CGMs. Once the member receives the device, any questions are handled by Levels’ support staff, not the doctor.

Telemedicine laws vary by state, but regardless of the different allowances, physicians have a duty to do what is right for their patients. While telemedicine appointments are a way to improve access to care, mishaps can occur when trying to treat more complicated patients over the phone.

The legal disclaimer protecting the company is quite extensive and defrays all the risk away from Levels and onto these doctors. Members must sign the following: “You acknowledge and agree that the affiliated third-party telemedicine providers are solely responsible for and will have complete authority, responsibility, supervision, and control over the provision of any medical services they may offer. You acknowledge that decisions relating to diagnosis, prescription, and/or treatment recommendations should be made between you and the health care provider. And you understand that throughout any communication or consultation with a provider via the Services, you are not entering into a provider-patient relationship with Levels…. You acknowledge and agree that you will not hold Levels or any Levels affiliate liable for any loss, injury or claim of any kind resulting from your failure to monitor, read or interact with these communications or for your failure to comply with any recommendations contained in theses communications.”

Not surprising, Levels does not accept insurance payments. More surprising, however, is their policy that members may not file their own claims to insurance companies for reimbursement purposes, stating “Please do not attempt to request reimbursement for Services through your insurance provider.”

Levels sells five CGM devices - two Abbott FreeStyle Libre devices and three Dexcom devices. Both manufacturers, Dexcom and Abbott, work with predictive insulin delivery systems using the patient data they collect, partnering with Tandem and Medtronic. In essence, the data collected from CGMs serves two purposes - relay blood glucose data to patients - then send that data back to the drug companies to create more products. Most patients are only aware of the first purpose.

Close collaborations between drug companies and providers is ethically fragile, and companies financially incentivizing providers to use their products is illegal. Levels has attempted to protect itself by offering more than one brand of CGM, but one of those brands - Abbott - has a storied history of offering illegal kickbacks. A quick Google search revealed three large cases, with the largest involving diabetes care products. In 2021, the DOJ sued them for offering free glucose monitors to ineligible patients, inducing them to order more testing supplies, and Abbott was forced to pay $160 million over Medicare fraud claims.

Levels collects a significant amount of personal health data beyond glucose levels, including dietary habits, exercise, and sleep patterns and encourages its members to import their data from Apple Health to their portal.

According to their privacy policy, they do not sell personal information, stating "We do not and will not sell your Personal Information to third parties. We also do not share your Personal Information with third parties for their own direct marketing purposes.” However, this does not prevent them from de-identifying and de-personalizing data and sharing it to third parties.

Levels is strategically domiciled in New York, where data sharing laws are more relaxed than those in California. California requires customers to opt-in to data sharing - New York does not. The only way Levels users protect their data is by sending an ‘opt-out’ email to the company’s data protection officer.

Data is the New Oil

Data is a trillion-dollar industry, and the value of healthcare data, in particular, is growing tremendously, both in terms of economic potential and strategic importance. The CAGR (compounded annual growth rate) of healthcare data is projected to be 13.85% from 2022 to 2030 – the market was valued at 32.9 billion dollars in 2021 and is expected to grow to 105.73 billion by 2030.

The buyers of health data are diverse, ranging from pharmaceutical companies, to health insurers, to data brokers who aggregate and sell this information. Tech giants like Google, through partnerships with health systems, leverage this data for developing health-related algorithms and services.

Pharmaceutical companies are very interested in acquiring healthcare data for developing and marketing new drugs but must navigate data privacy laws. The market for healthcare data involves both direct purchases and partnerships or data-sharing agreements, where data might be exchanged for services or insights rather than direct monetary transactions. Pfizer reportedly spends $12 million annually on health data.

On the darker side, stolen data is often sold on the dark web to identity thieves or for extortion. Healthcare data is among the most valuable on the black market due to its comprehensive nature. It includes not just personal identifiers but also detailed health records, which can be exploited for identity theft, medical fraud, and other illegal activities. For instance, individual medical records can sell for up to $250 each, significantly more than other types of personal data. Hackers value healthcare data fifty times higher than credit card data.

Healthcare data cyberattacks have led to huge settlements and negative publicity. In 2022, hacking was responsible for 80% of healthcare data breaches, highlighting a significant escalation from previous years. Merck paid out $1.4 billion following a cyberattack known as NotPetya in 2017, and a UnitedHealth data breach from February 2024 is predicted to cost the company $2.5 billion.

Based on available information, Eight Sleep does not sell personal data but states in its privacy policy and terms of service that it “may share or sell aggregated, de-identified data” for research, marketing, and promotional purposes. Users implicitly consent to these practices by agreeing to Eight Sleep’s terms when using the product or app. Levels, founded by Casey Means, follows a similar model, collecting extensive health data and potentially sharing de-identified data, raising concerns about commodification in a $105.73 billion healthcare data market projected for 2030.

This is America, and if you want to spend $4,000 on a mattress that cools your butt while sleeping, that’s your choice. But the rest of America shouldn’t subsidize it. Through TrueMed, co-founded by Calley Means, taxpayers effectively do. By leveraging tax breaks, TrueMed enables HSA/FSA purchases of the Eight Sleep system and other well-marketed but scientifically unproven “wellness” products, reducing federal revenue. For 2025, HSA contribution limits are $4,300 for individuals and $8,550 for families, with FSA limits at $3,300, fueling a $123.3 billion HSA market that TrueMed taps into.

On March 6, 2024, the IRS issued an alert (IR-2024-65) warning against companies misrepresenting nutrition, wellness, and general health expenses as medical care for HSAs, FSAs, HRAs, and MSAs. TrueMed’s model, which uses Letters of Medical Necessity to justify purchases, operates in this contentious gray area, drawing scrutiny for stretching IRS guidelines.

Calley Means’ vested interest in wielding government power reveals a glaring conflict of interest. As a special government employee at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) since March 2025, Means advises on the “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) agenda alongside Robert F. Kennedy Jr., whom he persuaded to drop his 2024 presidential bid and endorse Donald Trump. TrueMed stands to gain from policies expanding HSA/FSA eligibility, and Means’ HHS role amplifies his influence over such regulations. Federal ethics rules require SGEs to disclose financial conflicts and recuse themselves from decisions affecting their businesses, but Means’ advocacy for preventive care aligns with TrueMed’s mission, raising questions about bias. This mirrors a pharmaceutical CEO seeking bureaucratic power—does agreeing with MAHA’s message justify the conflict, or should leaders remain financially agnostic when wielding authority?

What is the power of data for Casey and Calley Means? Their mantra, “we need the data,” carries hidden implications: opportunity for innovation or exploitation. TrueMed and Levels collect vast health data, potentially monetized through de-identified sales to third parties like pharmaceutical firms, which spend millions annually (e.g., Pfizer’s $12 million). Calley’s media blitz blurs genuine health advocacy with corporate marketing, leveraging MAHA to promote TrueMed’s agenda. His HHS role, coupled with orchestrating RFK Jr.’s Trump alliance, intensifies concerns about data commodification and policy bias, especially as HHS faces layoffs and restructuring that could prioritize corporate-friendly reforms over public health.

Conclusion: Navigating the Data Economy

As we move forward, the health data industry must balance innovation with privacy, transparency with profit. Legal precedents exist for bureaucrats to disclose financial conflicts of interest, suggesting a similar standard might be applied to those in the private sector who influence health policy or collect significant amounts of personal health data. Whether or not you agree with the message of these health entrepreneurs, the question remains: should leaders in health tech be financially agnostic when their decisions can impact public health?

The power of data is undeniable, but so are the ethical, privacy, and security challenges it presents. As we harness this "new oil," the industry must ensure that the benefits to health and well-being are not overshadowed by the risks of data misuse or privacy invasion.

High tech snake oil salesman. Doubt Musk will be looking into this. Here's the new boss, same as the old boss, etc.

There is no savior on a white horse coming to rescue us. Yeah, a Skittle here, a Cheerio there.

Diversionary fluff, IMO. The mRNA will just roll on. Just my crabby little opinion. And I will not cheer tiny steps as if they were big and meaningful.

Dr. Bowden, thank you for all of your excellent research. I'm wondering why you didn't mention either Sam Corcos, CEO and co-founder of LEVELS, who's currently working for the DOGE team and as a Special Advisor to the Treasury Department, or Josh Clemente, who is credited with founding LEVELS, having previously worked as an engineer for Space X? Seems the heavy weights over at LEVELS are close to Musk. Is there a reason you chose not to include them in your piece?